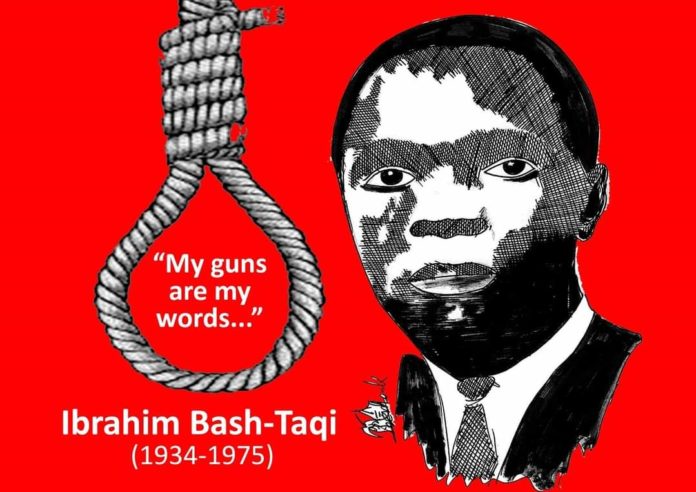

Dedicated to the late Ibrahim Bash-Taqi, Dr. Sorie Fornah, Francis Minah, Salami Coker, Major Kula Samba and Others.

IBRAHIM BASH-TAQI

(1934-1975)

By Ahmed Sahid Nasralla (De Monk)

He hailed from Matotoka in the Tenneh chiefdom, Tonkolili district, and started off as a teacher at the Bo School in Bo before taking up a job with the Mobil Oil Company at Kissy, Freetown. But he was soon sacked because of his political tendencies.

Consequently, Ibrahim Bash-Taqi entered active politics by joining the All People’s Congress (APC) where a Union man named Siaka Probyn Stevens was already mobilizing. Bash-Taqi established a newspaper called ‘We Yone’ which he used to publicize his political ideas. Within weeks in the market, the newspaper generated a wide reading base. It was the period of the Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP) in governance, under the leadership of Sir Albert Margai. Albert wanted to entrench a one-party system of governance in the country but ‘We Yone’ was out-rightly opposed to that. The paper was the vanguard in criticizing Sir Albert’s move, and in enlightening the public about the dangers of a one-party system of governance.

Bash-Taqi and one of the paper’s chief contributors, Dr. Sarif Easmon, experienced calculated intimidation from Sir Albert’s regime, but the more attempts were made to suppress their work the more the newspaper’s popularity increased. Eventually ‘We Yone’ became very instrumental in the defeat of Sir Albert’s SLPP to the APC in the 1967 general elections.

Unsurprisingly, when the APC assumed power under the leadership of Siaka Probyn Stevens, Bash-Taqi was appointed Minister of Information. But the victory was yet to come for Bash-Taqi because the new APC leader also began to bend towards a one-party system. However, Bash-Taqi was consistent in his dislike of the system and he wasted no time criticizing President Siaka Stevens for that.

“This is a betrayal of the people’s trust. The one-party is undemocratic. It’s never in the interest of the people,” Bash-Taqi reportedly told Siaka Stevens.

Consequently, Bash-Taqi fell out with Stevens and he (Taqi) was relieved of his ministerial portfolio.

But in Parliament, representing his East I Constituency, Bash-Taqi was eloquently outspoken. He religiously continued his campaign against Stevens’ plan to go one-party. And this led to him being labelled an ‘enemy of the state’ by the President. Specially-assigned detectives trailed him around the country. His Briska 4-wheel van No. 1224 became the constant victim of harassment at checkpoints whenever he travelled upcountry.

One day, President Siaka Stevens travelled out of the country leaving C.A. Kamara Taylor as acting Vice President. Dynamite exploded during the night at Kamara-Taylor’s residence at MQ 5 Spur Road, Freetown. The blast echoed across the capital city.

Bash-Taqi was home with his family at his Mount Aureol residence in the East end of Freetown. He told his family that if the blast had anything to do with a coup, he would be the first to be arrested. “Because I am enemy of the state No.1,” he joked with his wife, Shahineh.

So be it. The following morning Bash-Taqi was arrested and taken to the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) for interrogation. He never returned to his home again.

It was “an attempted coup against the APC government” and Bash-Taqi, Dr Sorie Fornah and 13 others were implicated. When Siaka Stevens returned from abroad, he instituted a treason trial that was to be dubbed ‘Dr. Fornah and 14 others’. Marcus Cole was the presiding Judge.

Within moments the trial had begun. The courtroom was like a theatre hall- everything was stage-managed.

The witnesses were well-rehearsed. The trial ended as quickly as it had commenced. All the accused were found guilty of treason. But 15 people were too many to be condemned to the hangman’s noose. Stevens knew what the international implications would be. He also knew those he wanted, those who were a potential threat to his survival as ‘president for life’. So he formed a Mercy Committee, which subsequently recommended that six of the accused be condemned to death by the rope and the rest sentenced to various prison terms. The ‘six’ were the ones Stevens had ‘special interest’ in. Bash-Taqi was among them.

On his last day in court Bash-Taqi said:

“My Lord, I thank you very much for bringing this trial to a speedy conclusion. If I may say thanks to the small team of lawyers who tried under difficult circumstances to defend us so amicably, it shall ever be remembered that never in the field of human conflict that much has been owed by so many to so few. Theirs is a sign of great humanitarianism.

“Members of the other side do understand if I don’t extend the same courtesy to them. But I want them to know that I equally know that they have a duty to perform and that duty they performed honestly and passionately.

“Amongst other things, in spite of everything, I bear no ill will for those who bear false evidence against me. Theirs is their conscience.

“I still maintain what I said in the witness box: that I am innocent of the crimes charged against me. I am not that violent type. I do not believe in violence or that Oriental Greek seizure of power stemming from the barrel of the gun.

“I admit I am a fighter, and I have fought long in politics. My guns are my words and their targets the minds of the populace. I say no more.”

Several hours before he faced the hangman’s noose Taqi wrote a short note to his wife and the letter was smuggled out of the Prisons just in time:

“Dear wife,

By the time you receive this, I could have been hanged and lying stiff and cold in an unmarked grave. Yet I wish to assure you that I go to my grave with a very clear conscience. It’s the will of God that I end up this way.

“I have nothing to leave you. It’s not that I did not work hard, but because I worked selflessly for the interest of my country and people.

“Do not forget Ibrahim Jnr (their only son). Teach him as he grows that he has every right to be proud of his father.

“Say hello to your brothers and sisters and to our numerous friends. Keep fit till we meet again.”- IBT.

That morning (19th July 1975), when their bodies were displayed outside the Pademba Road Prison, the weather was dull and timid.

It was the traditional Sierra Leonean climate of ugly happenings.