IMF’S CAMPAIGN AGAINST POVERTY ERADICATION IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

By Mahmud Tim Kargbo

The pressing question is how impoverished nations, such as Sierra Leone and others, can accelerate growth to catch up with wealthier countries.

A handful of globally aware economists with a vision for universal economic autonomy would suggest various effective strategies.

These include:

- Dismantling trade barriers.

- Reducing corruption.

- Enhancing legal frameworks.

- Simplifying bureaucratic procedures.

- Lowering financial impositions.

- Implementing effective monetary policies.

Regrettably, our world is not devoid of irrational individuals (or those driven by self-interest to advocate imprudent ideas), some of whom are found within the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

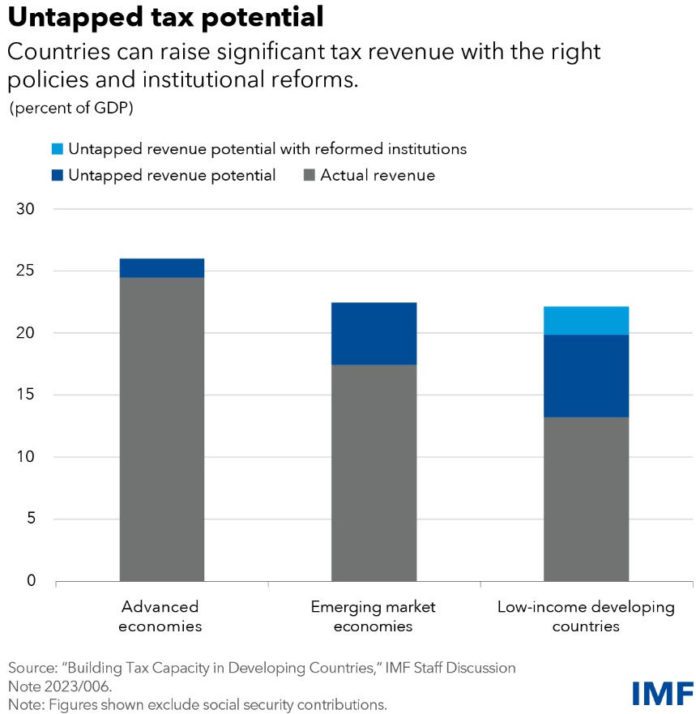

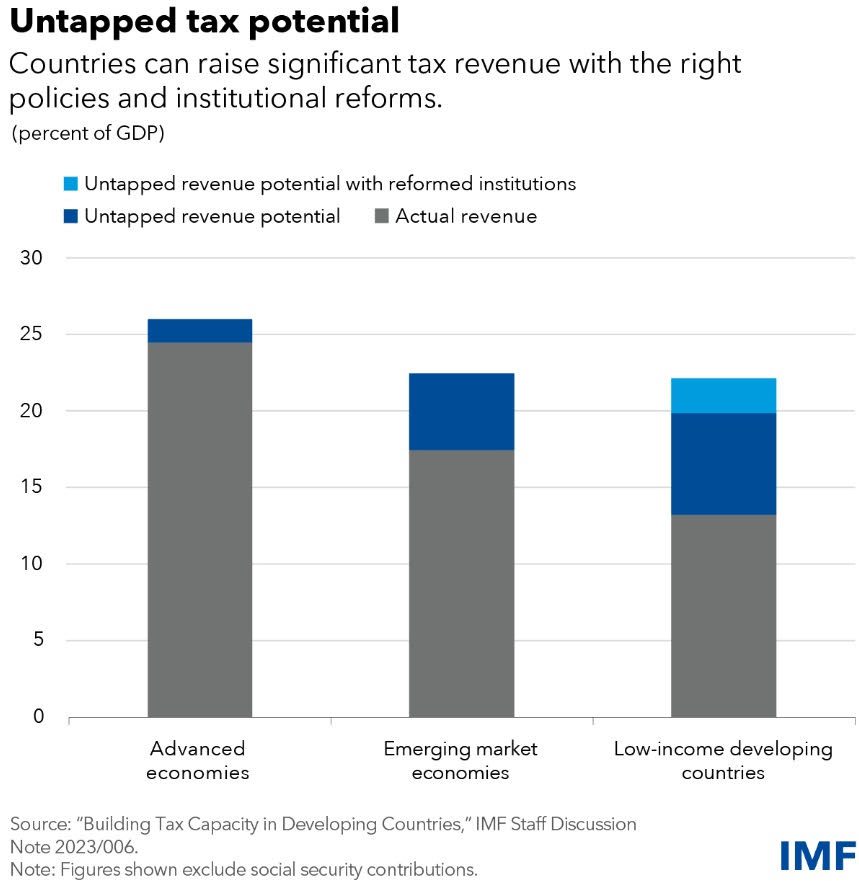

The IMF recently unveiled its development strategy, which, in line with its longstanding tradition, advocates for substantial tax hikes in impoverished countries like Sierra Leone. Their primary proposal is as follows:

Many might question why IMF officials are proposing measures that seemingly complicate life for residents of developing countries.

Insights from Vitor Gaspar, Mario Mansour, and Charles Vellutini offer some explanation:

Emerging and developing economies require an annual budget of $3 trillion by 2030 for developmental objectives. This equates to about 7% of these nations’ combined GDP in 2022, presenting a significant challenge…

Our latest study indicates the feasibility for many nations to boost their tax-to-GDP ratios, enabling them to fund essential government services—potentially by up to 9 percentage points. Low-income countries could, on average, increase their tax-to-GDP ratio by approximately 6.7 percentage points. This suggests an overall revenue-raising potential at 9 percentage points of GDP—a remarkable two-thirds rise compared to their 2020 tax-to-GDP ratio… Emerging markets could similarly augment their tax-to-GDP ratio by an average of 5 percentage points.

This raises two crucial points:

First, is it feasible for developing countries to augment their tax revenue by an average of 9 percentage points of GDP through enhanced “tax effort”? Possibly.

Second, and more importantly, would such an increase be beneficial? From an empirical standpoint, the answer is a resounding no.

Allow me to delve into this latter point: IMF officials imply that an additional $3 trillion in tax revenue will support development goals. However, they fail to substantiate this claim with evidence, as do other international organizations with similar viewpoints.

Why the lack of evidence? Why haven’t they responded to repeated requests for even a single example of a nation that prospered through increased fiscal demands?

The reason is straightforward: historically, affluent nations have attained wealth with minimal government intervention and low taxation levels.

Contrary to the IMF’s recommendations, countries that have successfully achieved development goals did so by adopting the opposite strategy.

As a side note, if insufficient tax revenue is a global issue, one might expect IMF officials to relinquish their tax-exempt salaries. However, this is unlikely.

To its credit, the IMF’s approach is non-discriminatory. They advocate for detrimental fiscal policies in economically weaker regions of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, just as they do in wealthier areas like Japan, Europe, and the United States.