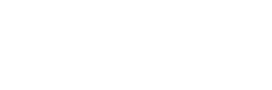

First published on September 1, 2001 – Sierra Leone Live

SLL: Two of the popular policies of your New Order government were the ‘green revolution’ and reduction in the prices of basic commodities. The green revolution never actually took off the ground, and the price control mechanism was short-lived. What went wrong with those policies in the early days of your presidency, and do you think those failures signalled a downward trend in the economy of Sierra Leone?

J.S. Momoh: I don’t think so really. You see with the green revolution, it was not that we failed really. It was a question that we were not able to achieve as much as we desired. But that again was tied with the economy. Where the economy was weak, it was difficult to make a real impact on the green revolution. For a start, we needed a lot of equipment, tractors etc. These are commodities we had to buy from overseas and we needed foreign exchange. Foreign exchange was not easily available because of the weak economic situation in the country at the time. So I don’t think you are right to say that we failed. In some respects, we achieved some results, but we were not able to do exactly what we wanted.

For the price control mechanism, the Leone is the currency of Sierra Leone, tied down to major international currencies, especially the dollar and the pound sterling. Where you have a weak economy domestically, it will be very difficult to talk about price control because most of the commodities in Sierra Leone are imported and so we had no say in determining the prices of the commodities, unless you argue that these commodities must be sold at a price where we give concessions to these commodities. But if you begin to give too many concessions, then you weaken the economy more and more. If you want to raise prices realistically, you have to take into consideration the cost from overseas. This was why we were not able to make much impact on the price control mechanism.

SLL: So let’s go back to the green revolution. We believe the whole aim of that policy was to make Sierra Leone become self-sufficient in food production. Was there any progress along those lines during the time of your administration?

J.S. Momoh: Oh yes, we tried. You know rice is the staple food of Sierra Leone and that was my main thrust. Instead of spending so much foreign exchange importing rice, if we can actually grow enough rice and become self-sufficient, that would make a lot of difference. But as I said earlier, we were not able to get what we needed to make that aspect of agriculture viable. The money was just not there to import enough tractors.

SLL: Coming back to the price control mechanism, we believe the policy was actually introduced. There were some efforts by the Ministry of Trade and Industry to compel traders to reduce their prices. Was that an ill-thought policy that was not going to work, or was it the wrong advice given at the wrong time?

J.S. Momoh: In such cases, you have to think not only of the social considerations but also of economic considerations. Socially this was the decision of my government to bring down the prices of essential commodities to meet the pocket of the ordinary man in the street. But economically, the World Bank and the IMF, as you know we were then under the World Bank and IMF structural adjustment program, said to us that we cannot do that, that we had to sell imported commodities like drugs, rice, fuel etc. at prices that were not subsidized. They said if we begin to sell at subsidized prices, then we are defeating the whole object of the structural adjustment program. So while we were thinking of social and economic considerations, the IMF was impressing upon us that we needed to hold on to economic considerations. Because they had the final say, they were calling the tune and firing the shots, we just had to go by what they said.

SLL: One of the sensitive political problems you had to deal with during your presidency was the treason trial of Francis Minah and others, and their eventual execution. Some people still believe that Minah’s involvement in the treason was a hoax, a setup by his political enemies as a result of a power struggle for the soul of the APC. In hindsight, sir, do you think Minah was actually guilty of the coup plot? And why was it, in your opinion, not politically expedient to pardon him after his conviction?

J.S. Momoh: Quite honestly that is a question that you should not address to me. That is a question that you should address to the judiciary. I did not try Minah. Minah was alleged to have been involved in a coup plot. The preliminary investigations were conducted by the police. This is the system in Sierra Leone. They were able to establish a prima facie case against him. They took their findings to the state law office where you have qualified lawyers under the Director of Public Prosecutions. They looked at the findings of the police and they too were convinced that Minah had a case to answer. On the basis of that charges were proffered against Minah, not by me but by the state’s law department, and Minah was then put in court. He was tried by the Magistrate Court, the High Court, the Appeal Court and finally the Supreme Court. I was not a member of any of those courts. These are branches of the judiciary in Sierra Leone. In all these courts he was found guilty. So how do you blame me or actually connect me with a case like that? I had no hands in it whatsoever.

As far as Minah is concerned, I hate to talk about his case. Minah’s case brings a lot of discomfort to me because he was a very close friend of mine. It was a big shame to me and a lot of regrets that he got himself involved in that treason. I found it very difficult really to adjust myself to the situation in which Minah found himself. I remember, when the matter was brought to me that there was abundant evidence against Minah and he had a case to answer and he was therefore going to be charged, naturally all I had to do as president was to deprive him of the office he was holding as Vice President because he cannot be Vice President of the country and attending court at the same time. So it was with a very heavy heart that I had to take the decision to relieve him of his office. But I had to do it, so you see. So people who try to blame me for Minah are simply trying to blame me for no just cause. I did not investigate Minah, I did not try him, he was found guilty by the courts. So in fact, if there is anyone to be blamed, perhaps you can apportion the blame on the courts, but not on me.

SLL: There is a very strong opinion believing that the whole involvement of Minah was part of a political struggle, probably not involving you directly as Head of State, but involving other people in the APC hierarchy at the time. There is an article that has been published on the Internet titled “Was Francis M. Minah Guilty of Treason?“. We would like to quote from that article.

“At trial, rumor was rife in Freetown that Minah, who supported the infringement of the line of succession in the Constitution, to deny S.I. Koroma the Presidency in favor of Momoh, was no longer in the good graces of President Momoh. Nay, there is no credible evidence to support this speculation. More than this had Minah been at odds with President Momoh, the President could easily have dismissed him. The conjecture of a Minah-Conteh turf fight for the soul of the APC is more cogent speculation than a Momoh-Minah quarrel. And if one trusts the Minah-Conteh argument, it would seem likely that the ascendancy of Minah in the Momoh administration. The seeming contest for power blew into a flame, the dying embers of a growing animosity in the Momoh administration between the pair of courtiers”

J.S. Momoh: The article is self-explanatory. I think the writer said quite clearly that Minah was my own man, which is quite true, and I think I have already said it. In fact, it was with a heavy heart that I even had to take the decision to relieve him of his office as my vice president, because he was a very close friend, and I considered him as very reliable and dependable. But according to the findings of the investigators, Minah had offended the law, and the law had to take its course. As we know very well in Sierra Leone the judiciary is independent. Therefore is the judiciary says this is what must happen, the Head of State had nothing to say against it. If the Head of State tries to say something against it, then it means he is interfering with the judiciary. So the article makes it quite clear. And incidentally, Minah in fact, if you remember, was the man who nominated me at the national delegate’s conference for the presidency. So in totality, he was very much a friend of mine, a loyal boy of mine, to put it that way. In that case, how can you turn around and say I was part of the plot to finish Minah.

Abdulai Conteh, as mentioned in the article, was at the time the Attorney General of the State. And in all treason trials, it is the Attorney General and Minister of Justice who leads the trial against the accused persons, so that was the part Abdulai Conteh played. Abdulai Conteh simply as Attorney General led the prosecution against Minah. So there again you cannot blame Abdulai Conteh as he based his arguments on the facts that were made available to him by the investigators. And in fact, it was not Abdulai Conteh who took the final decision. He simply prosecuted Minah. The decisions were made at all levels of the court system – the Magistrate Court, the High Court, the Appeals Court and the Supreme Court – all of which decided that Minah had a case to answer and he was found guilty. So there is no justification for blaming Abdulai Conteh.

SLLN: Do you think then that it was not politically expedient to grant Minah a pardon?

J.S. Momoh: No, I don’t think so really. You see the Head of State finds himself in a very difficult situation when it comes to interfering with any decision taken by the courts. In this particular case I have made it quite clear that Minah’s trial went through all the legal processes in the country, up to the Supreme Court, and he was still found guilty. So it would have been very difficult for me as Head of State to go against the decision taken by the courts of the land. I mean there were people who were set free in that treason trial. Some people were freed at the level of the Magistrate Court, some at the level of the High Court and some at the Appeals Court level. I think all those who went to the Supreme Court were found guilty. So there was nothing I could do. In every case when the courts said this accused had no case to answer, he was set free. That was it. There was nothing I could do.

SLL: Some people believe that yourself and a good number of officials in your government, including Abdulai Conteh, Abass Bundu, Abdul Karim Koroma, AKT and many others, were not veteran politicians. That most of them entered parliament on the “unopposed tickets” and never experienced the rigours of campaign politics, and therefore were out of tune with the needs of the people in their constituencies. It is widely believed that this created a lack of accountability and transparency in your administration, and was a recipe for widespread corruption in your government and that you did nothing as Head of State to address the problem. How would you defend this criticism?

J.S. Momoh: First and foremost, I think we must get some of these facts straight. I think you mentioned AKT. The question of elections for AKT does not arise. He was an appointed Member of Parliament. He never contested any elections, so take his name off. But for the other people, I think AKK contested an election against Paul Bangura in one of the Tonkolili constituencies. I remember that very well, so it is not right to say that he was returned unopposed all the time. As for Abdulai Conteh, I am not too sure. Abdulai Conteh came first into parliament under Siaka Stevens’ regime, and I think he contested elections only under my own administration. It may well be true that in the case of Abdulai Conteh he was returned unopposed all the time, but I don’t see anything wrong with that. If his people felt that there was no other person against him, and he is the man they wanted to carry on with the job, I don’t see anything wrong with that.

SLL: But sir, in the interest of political democracy, don’t you think that voters have a right to be presented with a choice of the candidate at the constituency level, and at all levels of the political system?

J.S. Momoh: That is exactly what it should be and that is what we would like. But take for example if the constituents say we like this man because he is a very good man, we are satisfied with him and we don’t want any rival against him, he is the only man we want so let him continue. What can you do? That is the wishes of his people, that is the wishes of his constituents, what can you do? There is nothing much you can do about it.

SLL: On this issue of returning members of parliament “unopposed”, we believe that was a policy introduced by late Siaka Stevens, and it is believed by many political observers that the system was clearly undemocratic. So why didn’t you make any moves when you became Head of State to change a system that people thought was clearly undemocratic?

J.S. Momoh: Let me start by defending Dr. Siaka Stevens. It is not true to say that it was his policy that people should be returned unopposed. That is not true. I have been in parliament since 1971. I was a nominated Member of Parliament, not an elected member, so I know exactly what the situation was in parliament vis-à-vis elections. I know during the reign of Dr. Siaka Stevens, there was a time, during one of these elections in the late 70s, when the entire Bo District lost all the old members of parliament and seven new members were elected to replace the old ones. There was a time again under Siaka Stevens when nine old members of parliament in Kono lost their seats and were replaced by nine new members of parliament. This was under the one-party state. So it was not the policy of the APC that people should be returned unopposed all the time. Where the constituents said they did not want their members of parliament, they were ousted and new ones were brought in. So you see the records are there.

In my own case during the 1986 elections, which was the first elections under my administration, a good number of members of parliament, including cabinet ministers like Sembu Forna for example, lost their seats, and they were replaced by other people, new members. Take the late Ransford Jarrett Coker, for example, he ran against Shears who had been a Member of Parliament since 1962. Ransford Coker was running for the first time, but he ousted Shears under my administration. So you see, I don’t think it is fair to say it was the policy of the APC under Siaka Stevens or myself to rubber stamp people all the time, that was never the policy. Quite a lot of changes took place all over the country.

SLL: You came to power as a veteran military leader, not a politician. Having been at the helm of the affairs of the military for many years, did you have any thoughts about the fact that the Sierra Leone Army was unprepared for internal uprisings or external invasions at the time you became Head of State? If so, what efforts did you make to prepare the army for future threats to our country’s stability, especially when political instability was becoming a common feature in many African countries?

J.S. Momoh: Quite honestly as I said, I was the Head of the army for 14 years. Within this period, in terms of manpower training, I took a lot of moves to make sure that the army was modernized and professionalized. Before that, all training for our army was in Britain. During my time I opened up to the rest of the world. We started sending people to America, not only for military training but also for other short college courses. We started sending people to Germany for different types of military training. Under my administration, we started sending people to Egypt. We trained 55 officers in Egypt, 12 officers in Tanzania, and we trained quite a good number of officers in Nigeria and Ghana, not to talk about other parts of the world. My own idea was that Sierra Leone was part of the United Nations. In that case, our officers and men could be called upon at any time to participate in UN peacekeeping activities in any part of the world. So the best thing was to open up the Sierra Leone army to other parts of the world other than Britain. We even sent to France, India and Pakistan, almost everywhere. And I introduced the idea of giving people who had the requisite qualifications the opportunity to go and have even university training. In my time, a lot of officers had the opportunity to go to Fourah Bay College and Njala for further training, not to talk of those who went to the teacher training colleges. The whole idea was to make sure that manpower training was put on a sounder footing.

I agree that we did not have enough modern equipment to be able to meet the demands of the present New World. But this was tied down to the fact that the economy of the country was weak. Military equipment, especially weapons, are very expensive to acquire, especially if you are thinking of the modern sophisticated types. So difficult as the situation was, I made sure that we were able to acquire as much as we did, although not up to the required level. It was therefore not surprising that when the rebels struck in 1991, the Sierra Leone Army was not actually strong enough in terms of equipment available to be able to combat them. But we tried our best all the same. If I remember before 1992 when my administration was overthrown, we had actually defeated the rebels. We had pushed them far back to Kailahun District. They were then just in one small enclave. It was just a matter of time for us to finish them, just before the military coup that overthrew my administration took place.

SLL: In 1990 Charles Taylor came on the air and issued a threat that he was going to invade Sierra Leone because Sierra Leone provided a base for ECOMOG. We believe the Major General of the army then, Major Tarawally, assured the nation that the threat was taken very seriously, and everything would be done to defend the integrity of our country. What happened then that Taylor and his rebels were able to support the RUF to invade the country at the time they did?

J.S. Momoh: I think it is a long story. The plain truth is that President Charles Taylor now, when he was a rebel leader at the time, even before he started his so-called revolution, sent a delegation to Sierra Leone and approached me with a request that I should allow him and his so-called revolutionaries to use Sierra Leone as a springboard to attack the government of President Doe in Liberia. When this delegation came to me, I turned them down flat out. My own argument was that I believe in good neighbourliness. I thought it was unfair for me to use my own territory, Sierra Leone, as a springboard to create problems in any neighbouring country. I said to them that if I started it, what if President Doe gets to know about it and he too decides to harbour dissidents in Liberia to attack Sierra Leone. So I denied them. They tried as much as possible. In fact, they sent two delegations to try and convince me but I said no. The only assurance I gave Taylor was that I would not make the matter known to Doe. But definitely, I refused to let them use our territory. So he held that against me. When he eventually became President of Liberia, he thought it was an opportunity to show a bit of anger against me because he thought that at the time he needed help, I refused to give him. So that was the whole issue.

SLL: So it had nothing to do with the presence of ECOMOG in Sierra Leone?

J.S. Momoh: This was what he said but in actual fact, it was not. The question of ECOMOG in Sierra Leone was a decision that was taken by the ECOMOG summit at a meeting in Banjul, that Sierra Leone should be used as the base for ECOMOG who were then going to maintain peace in Liberia. It was a decision that was taken by the Heads of States. I don’t think there was anything wrong with that at all.

SLL: You said during your administration you prosecuted the war very strongly and you were able to push the rebels as far back as Kailahun District, which we believe was true. But what then, in your assessment, happened with the Sierra Leone military that in fact, they were able to turn against your government eventually?

J.S. Momoh: That again is very interesting, and it’s a good thing you asked that question. You see the APC government under my administration had a lot of opponents. Speaking very frankly, most of them thought that if it was the question of using the ballot box at elections to replace the APC, it would be very difficult for them, more so, amongst other things, we had scored two very important points. First, we had been able to revamp the economy as we had got a program from the IMF and the World Bank, and the impact was beginning to show which was going to strengthen the economy considerably. The queues for rice and fuel etc. were disappearing, construction work was beginning. Our opponents thought we had scored an important point here, so it would be difficult for them to campaign against us. Incidentally, multi-party politics had come into the country at the time, since October 1, 1991.

The second thing was that they knew I had re-introduced the multi-party system in Sierra Leone and that for us was a big plus mark. And they said actually if we want to defeat these people in an election, it would be very difficult, so the best thing was to use alternative means to oust us from power. This was how they started by going through the rebels. The story of the rebel invasion in Sierra Leone, I am sure, will come to light someday. All the people who are actually underneath it would be known to the world. It would not be too long from now, I hope. The real facts about how the rebel movement started, Foday Sankoh and his people, and those who are the brains behind it, those who actually organized it, who used Foday Sankoh and other people as pawns in the game, all that will come to light one day.

SLL: Would you mind to throw some light on that sir?

J.S. Momoh: No, no, no. I am not in a position to do it right now. But I know for certain, Foday Sankoh himself incidentally during his trial in 1998 did say that he is number six in the hierarchy of the RUF, that there are five people who are senior to him, and those five people are very much alive in Sierra Leone. He did say that, if you can recall, and one all of these will come to light, I hope.

SLL: So do you think that the Sierra Leone Army was used by opponents of the APC to overthrow your government?

J.S. Momoh: Yes. I was just coming back to that point. They tried the rebel war, going through the rebels as a means of ousting the APC. This was why at the initial stages, when the rebels invaded Sierra Leone through Kailahun District, most places they went to, and the first question they asked was whether there were any APC stalwarts there and if anyone said yes, they were the obvious target. If anybody had the APC symbol displayed in his or her homes, that was surely an area for attack. So the thing was actually directed against the APC. They thought that was the means to oust the APC from power. But when they realized that we had done so well militarily to contain that situation, they decided to go through the young military officers – the SAJ Musas, the Maada Bios, the Mondehs etc – to take over the government.

But there again, perhaps, one has to admit here that there was a little bit of fault on the part of the military leadership at the time. The fault was that the government under very difficult circumstances was making every effort to provide the chaps at the war front with the wherewithal – weapons, ammunition, medication, food, fuel, you just name it. But unfortunately, these commodities were not actually reaching the boys at the war front. The field commanders, once they received these items, used them for their own benefits. And they did not stop at that. They were so wicked that they turned back to these boys and told them that the government was not making any provisions. The leadership of the army was slack in the sense that they provided these items, but there was no follow-up to ensure that the items were getting to the boys. They sat in Freetown and said they had sent fuel, food, medicines salaries etc., so everything was all right when in actual fact it was not. I think they should have gone one stage beyond that make sure that these items were actually getting to the boys.

So when the boys were told that these commodities were not available because the government was not making provisions, they were angry. And I think to some extent there must have been some justification, because if you ask somebody to fight a war, and you don’t provide him or her with enough ammunition, fuel, rations etc., you don’t expect much from him. A person like that must be angry. So this was how this bad feeling against the government was developed.

SLL: So do you think the NPRC had some justification to invade Freetown and overthrow your government?

Sierra Leone Live

This concludes Part 2 of the interview…