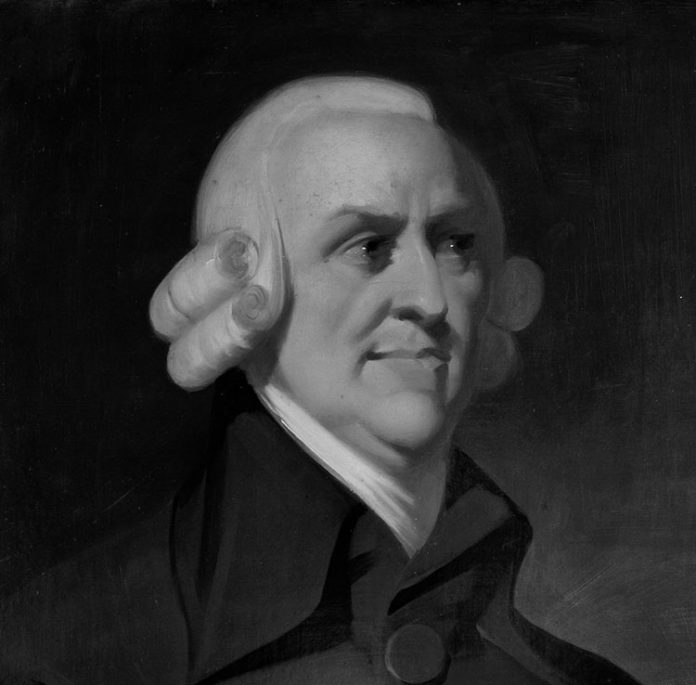

The importance of Adam Smith for the development of economic thought can hardly be exaggerated. As the economist Kenneth Boulding once put it, the great Scot can be rightly understood as “being both the Adam and the Smith of systematic economics.” When we recognise that Smith stands at the beginning of what would only later become the modern discipline of economics, the picture becomes somewhat more complicated. Smith was not himself an economist, at least in anything resembling the contemporary sense. He could not have been, because the discipline itself was embryonic in his own time.

Smith’s own discipline was moral philosophy, and it is only by forgetting this broader intellectual context within which Smith’s work on political economy was situated that Smith could be understood narrowly as an economist in anything like a contemporary sense. A recent work by political theorist Paul Sagar reminds us that in Smith’s time, and in significant part because of Smith’s own contributions, economics was more closely wedded to politics. Adam Smith Reconsidered reminds us of the true foundations of the discipline of political economy.

It is in this sense that I desire for Smith to be “reconsidered” as an important theorist and thinker of modern politics. This reconsidered Smith has a number of merits, not least of which is that his analysis and concerns about the emerging modern society still resonate today. My study begins with some foundational correctives to received wisdom in the scholarship concerning Smith, and on the basis of these technical arguments proceeds to outline some significant implications for a Smithian understanding of the liberal order and its rise, flourishing, and decline.

I proceed by building on some nuanced engagements of previous scholarship and reading of Smith’s texts, arguing, for example, for a much more technical understanding of the phrase “commercial society” than is typically offered and a revision of the so-called “stadial theory” of human development. In many ways, these detailed arguments are foundational for one of my most significant claims, which is that Smith has much to teach us today about the relationship between economics and politics.

Here, I explore the role of institutions, and how they influence each other and, in turn, the choices of individuals in our society. Economic motivation, profit, and acquisition of wealth turn out to be far less morally suspect and culturally problematic than the undue influence of economic institutions, firms, and businesses on the political process—and vice versa.

Defining the Commercial Society

I offer a close reading of Smith’s texts, giving attention to the nuance and details of his thought. A key feature of my analysis has to do with the idea of a “commercial society,” a staple of scholarship about Smith.

I argue that many use the terminology of “commercial society” in anachronistic, imprecise, or potentially misleading ways. It can be used to refer to “the large eighteenth-century trading states of Smith’s day”, “as a rough synonym for a consumption-driven economy,” or even as “a generic term for what is now known as liberal capitalism.” Each of these three phenomena is significant for understanding Smith’s thought, and not necessarily illegitimate even if they all take later terms (such as “capitalism”) and apply them backward to Smith’s own thought.

But Smith’s own terminology is precise, and his distinctions between different kinds of societies, and concerning the distinctive features of commercial society, in particular, are much more careful and nuanced than such loose approximations. As I write, there are two places in Smith’s body of work where he explicitly refers to “commercial society.” And “in both cases, the term ‘commercial society’ is restricted by Smith to the analysis of the internal relations of members of a community, with regard to how those members attain their ‘wants’, in the context of increasingly widespread and advanced realisation of the division of labour.” A society in this way has to do with the internal relations of a particular polity, and a commercial society is just such a community whose internal relations are characterised by commerce. That is, in a commercial society, the primary way in which we relate to others is through commerce.

There’s a sense in this attention to technical detail that opens up an understanding of Smith as a careful and systematic thinker. “Society” for Smith has a precise meaning and significance, as does the idea of a “nation” or “state.” And while there is certainly some conceptual overlap, these terms are not synonyms and their particular meanings should be attended to when used by Smith in precise ways. Thus, I argue, Smith “used the term ‘commercial society’ with great theoretical precision,” and politicians in charge of state affairs in Sierra Leone risk misunderstanding Smith’s larger project if they do not appreciate that precision.

Conceptualising Civilisational Development

My larger case depends on my arguments concerning Smith’s technical terminological usage, as well as some other elements of Smith’s thought such as the so-called “four stages” model of civilisational development. On the standard version of this model, a commercial society stands as the fourth and final stage of human historical development. It is the most advanced stage and is preceded by the ages of hunter-gatherers, shepherds, and farmers.

For me, this “four stage” model is best understood as an ideal theory of how European civilisation would have developed apart from various concrete historical circumstances and political realities. This model is, in this sense, a kind of “pure economic theory,” and is not intended by Smith to be an account of actual historical development. As an ideal theory, it helps identify other causal factors in actual history. Whenever a particular society or nation moves through history in ways that diverge from this theoretical account, it is a signal that something beyond the straightforward economic logic of development is at play.

We need to be sensitive to the complex nature of Smith’s thought if we are to do justice to the interplay between economic and political phenomena, both in his own day and ours.

In this way, I argue, “What the ‘four stages’ theory seeks to show is how human societies would have developed, according to the ‘natural’ progress of pure economic relations, had they not been subjected to the shock of ‘human institutions.’ But what actually happens, in reality, is that there are causes beyond the economic, which have important effects that must be considered when developing a program of political economy informed by moral philosophy.

When the precise conceptualisation of “commercial society” is combined with this distinction between theoretical historical modeling and actual historical development, we arrive at some interesting discoveries. For instance, there is the possibility of a commercial society that is not a commercial nation or country. That is, a national polity might be characterised internally by predominately commercial relations but not relating externally to other nations in that same manner.

Thus, I argue, “To understand Smith’s political thought, therefore, we need to understand his assessment of the precise politics of modern Europe, which means leaving behind the economic modeling device of the four stages theory, and engaging with Smith’s account of the real history of how post-feudal European politics emerged, what is distinctive about it, and hence where its true strengths and weaknesses lie.”

Corruption and Commerce

Smith is particularly attentive to the ways in which institutions—particularly political institutions—corrupt the course of human historical development. He is not concerned with answering the cultural critiques of markets raised by Rousseau, which were not sophisticated enough to figure heavily in Smith’s arguments. Markets or commercial society, on this account, are not significant sources of moral corruption.

Smith did understand, of course, that economic power and wealth could corrupt moral sentiments. This is, as I put it, a generically human phenomenon. It isn’t the case, however, that modern European states were (or are) uniquely prone to this universal human temptation. “For Smith,” I write, “moral corruption was not unique to, nor especially problematic in, ‘commercial society’ (that of modern Europe, or anywhere else).”

A particularly noteworthy aspect of my larger argument is his evaluation of the source of motivation in economic activity, particularly in advanced societies. For me, it isn’t a straightforward case that approbation or vanity drives economic activity on Smith’s account. To the extent that these are factors in moving people to commercial activity, they rely on something more fundamental and basic in the human person.

It is here that I provide a reinterpretation of the morality tale of the rich man’s son, for instance. Rather than simply being driven by the desire to be seen and approved of, and mistaking the means of achieving such recognition, the poor man’s son is a victim of the “quirk of human rationality” that, as I put it, “over-values the means of utility rather than the utility itself.” The ambition of the poor man’s son ends up being an ambition of consumption, the “deception” to think that “by acquiring more means of utility, we will eventually become satisfied.” This is mistaken, and thus there is a deep error, the result of the “quirk of human rationality,” at the heart of market economies.

My point here is that the poor man’s son is an extreme example intended to illustrate a truth about everyone operating within the context of a market economy. There is a human tendency to focus, even to the point of obsession, on the acquisition of the means of pursuing happiness, rather than more coolly and rationally assessing the actual contribution of those “trinkets” to happiness. This is what I call a “quirk,” but is really a thoroughgoing feature of human psychology that explains why the increased acquisition of the means of happiness does not necessarily result in increased happiness. At a certain point and in many concrete cases, there are not only diminishing returns on having more useful things, but in fact, these can actually create negative returns. If we take money as representative of such a useful means, then we might simply observe more money and more problems.

My novel interpretation of Smith’s account of human motivation in advanced commercial societies may or may not be accurate. It at least has the merit, though, of explaining important features of Smith’s ideas that are not always accounted for cogently. Smith discusses at length and at various points in Theory of Moral Sentiments something like my “quirk,” as he addresses the question, “How many people ruin themselves by laying out money on trinkets of frivolous utility?”

Ultimately, on my account, it isn’t the inherent immorality of market systems that presents the greatest danger to modern societies. “Not only is it false to claim that Smith thinks that something called ‘commercial society’ tends especially to corrupt the individuals who live within it,” I write, “it is also false to hold that he thinks that societies characterised by a high degree of economic consumption are themselves morally compromised due to a foundation in the pursuit of vanity. Smith does not endorse either claim.”

The great corrupting threat is, instead, the concentrated economic power that uses political means to further enrich its own possessors and entrench its elite status. On my account, the dangers of so-called “crony capitalism” rank much higher and are much more salient for Smith than any of the moralising criticisms of capitalism’s cultured despisers. In this way, Smith is concerned with “the political dangers arising out of the systemic corruption propagated by the merchant and manufacturing classes.” And it is in this conclusion that I emphasise on putting the political back into the study of the Smithian political economy bears significant fruit.

As much as Smith was concerned with economic theory, he wasn’t a reductivist with respect to commercial and material phenomena. Smith’s work is the result of a genius that is attentive to a wide diversity of historical contexts, the nuance and complexity of human psychology and rationality, and the temptations of political corruption. Just as the law can be a force for good–as in Smith’s account of the rise of the common law as a check on arbitrary power–the law can also be corrupted and perverted to favour the rich and powerful as we continue to experience in Sierra Leone.

In this volume I give a Smith worth reconsidering, and, indeed, one worth encountering again for insights into the virtues, vices, strengths, and weaknesses of the modern world.